You don't need a publisher

Self-publishing has grown beyond vanity press into a sustainable business model

Webcartoonists and independent comics artists have been self-publishing successfully for decades. You can, too.

I have to admit, my teeth grind a little when I see a twenty-something comics artist who is yearning for a publishing contract. And that goes double for a comic-strip creator who’s pining for a syndicate to pick up their feature. Back in the nineties, when publishers had the inside track for both printing and distribution, this was definitely the better choice.

However, since the early 2000s, creative people have been building their readerships online and monetizing them directly by producing and selling books and other merchandise. Moreover, since creators aren’t sharing the profits with a publisher, it’s possible to build a financially secure business on a much smaller audience than traditional publishing requires. Creators with niche readerships can thrive in today’s self-publishing landscape.

I know because I was there from the start

We’re living in the New Golden Age of Comics. There has never been a better time to create comics, and there has never been a better time to be a comics reader. Oddly enough, this comes as a surprise to many comics creators! They’re still placing their hopes on promises that were never meant to be kept. And living in a world that hasn’t existed for over twenty years.

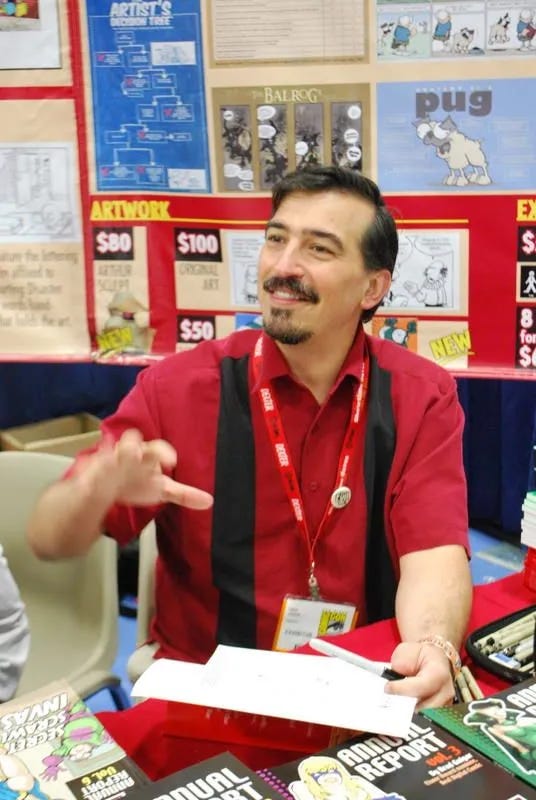

I know because I was there twenty years ago when the New Golden Age started.

Picture it: Philadelphia, 1998. Or as my sons refer to it: “The late nineteen hundreds…” I had always wanted to draw comics. It was always my One Thing. I never had a phase where I wanted to be a firefighter, a nurse, or a chef. I wanted to tell stories by putting words and drawings into boxes. The senior thesis for my BFA degree was all editorial cartoons and comic strips. I landed a job as a newspaper graphic artist on the advice of a political cartoonist who told me that it was the best way to break into editorial cartooning — work in the newsroom and submit political cartoons on the side.

I had taken those comic strips from my senior thesis and submitted them to several newspaper syndicates. Syndicates were companies that sold features like comics, puzzles, columns, and other features to newspapers. Traditionally, they took about 50% of the profits and, in many cases, claimed ownership of the copyrights involved. However, getting signed by a syndicate was a clear path to financial stability for anyone who could land a contract. Syndicates received thousands of comics submissions a year. From those, they’d launch one or two. The rest got copies of rejection letters addressed “To whom it may concern.”

I had a drawer full of those rejection letters. I still do, by the way. A large chunk of my career has been focused on punishing those companies for sending me those slips. A twenty-three-year career in comics, powered by spite.

Then, one day, a CD marked AOL landed on my doorstep. Using this disc, I could install software on my computer that enabled me to reach the World Wide Web — an intricate network of sites that offered everything from cat pix to chat rooms.

And the very first thing I used AOL to find was a way to publish my own work. OK… it may not have been the first thing. Nevertheless, I quickly realized that I could use this “Internet” to publish my comics without a syndicate. And that’s exactly what I did. On February 14, 2000, the first “Greystone Inn” comic strip appeared on a GeoCities site, kicking off a Monday-through-Saturday publishing schedule that would last for the next twelve years with one central, abiding purpose — to build an audience big enough to convince the syndicates that they had made an unforgivable mistake in sending Brad Guigar a rejection letter.

Twenty-three years of spite.

The year 2000 saw a tremendous swell in cartoonists who had figured the same thing out. Comic strips, in particular, were perfectly suited to a pre-social-media Internet. People back then searched for sites that delivered the kind of content they wanted and then bookmarked them when they found them. Many folks opened a list of bookmarks on their computer as they started their day and made their way through it as they worked. A daily comic strip meant you could make your site habit-forming, and that was good for building an audience — and it was good for generating ad revenue.

We called ourselves webcartoonists, and we immediately set out to replicate the success that we had seen in newspapers. We formed syndicates, offering our combined pageviews to advertisers and then splitting the profits. Keenspot was one such syndicate. Modern Tales, which actually worked on a subscription model, was another. But trusting your credit card number on a website — even for a micropayment — was asking far too much of people in the early 2000s.

Eventually, we realized that we didn’t need syndicates at all. Technology had progressed to the point at which launching a website and connecting to an ad network was easily accomplished on a Saturday afternoon. And, in the mid-2000s, an entire generation of self-employed cartoonists was born.

We taught ourselves business. We taught ourselves cash flow. We learned how advertising works. And marketing. We learned to pay taxes as sole proprietorships. And when our audience was ready to support it, we taught ourselves self-publishing. We took pre-orders, used that money to fund print runs, and sold those books directly to our readers. We ran online stores selling print-on-demand T-shirts and mugs. And, very notably, we gathered in forums and messageboards and shared the knowledge we were accumulating with each other. It was a rising tide that lifted all of the boats.

We realized that we didn’t need a syndicate, a publisher, or any other gatekeeper to give us their approval. We went directly to our audience and got all the approval we needed. And that’s when the new Golden Age of comics truly blossomed. Voices that those gatekeepers had previously shunned could now find their audience without intrusion. That means that comics — and the group of people who created them — became richer and more diverse as a result.

In a few years, Apple would make micropayments cool with the iTunes store. Kickstarter came next and revolutionized pre-orders. Patreon followed, providing a life-changing pathway for creators to seek financial stability on a subscription basis from those who love their work. Internet technology improved to the extent that longform comics could take root. Social media, in particular, made it much easier to build an audience without updating daily.

Today, a comic creator can cultivate an audience, build a business, and work towards a sustainable income… using little more than their talent, skill, and smarts. No publishers, no syndicates, no gatekeepers.

Part Two…

Think before you sign

I do a weekly podcast called ComicLab, which I co-host with another cartoonist who was there in the “late nineteen hundreds.” Our show has been compared to the NPR radio show, “Car Talk” — but for cartoons. Our listeners ask us questions, and we do our best to answer them, all the while poking fun at each other the way that only close friends with a 20-…

This was adapted from a live presentation I gave at Villanova University in September 2023.

😹😹😹 "and he hates Mondays and loves lasagna!"

Great post! I've learned what your talking about the hard way.